|

| Hiroshige, Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido. No. 26: Kakegawa |

I visited Japan in 2017 and 2019, on the second occasion with Fred, as well as my partner (with whom I’d travelled in 2017) and her son. Like most people who come for the first (or second) time, we took the Shinkansen – bullet train – from Tokyo to Kyoto on the line called the Tokaido. Volumes have been written about the wonders of Japan’s Shinkansen system. It is, I think, something that should be experienced at least once in everyone’s life if possible.

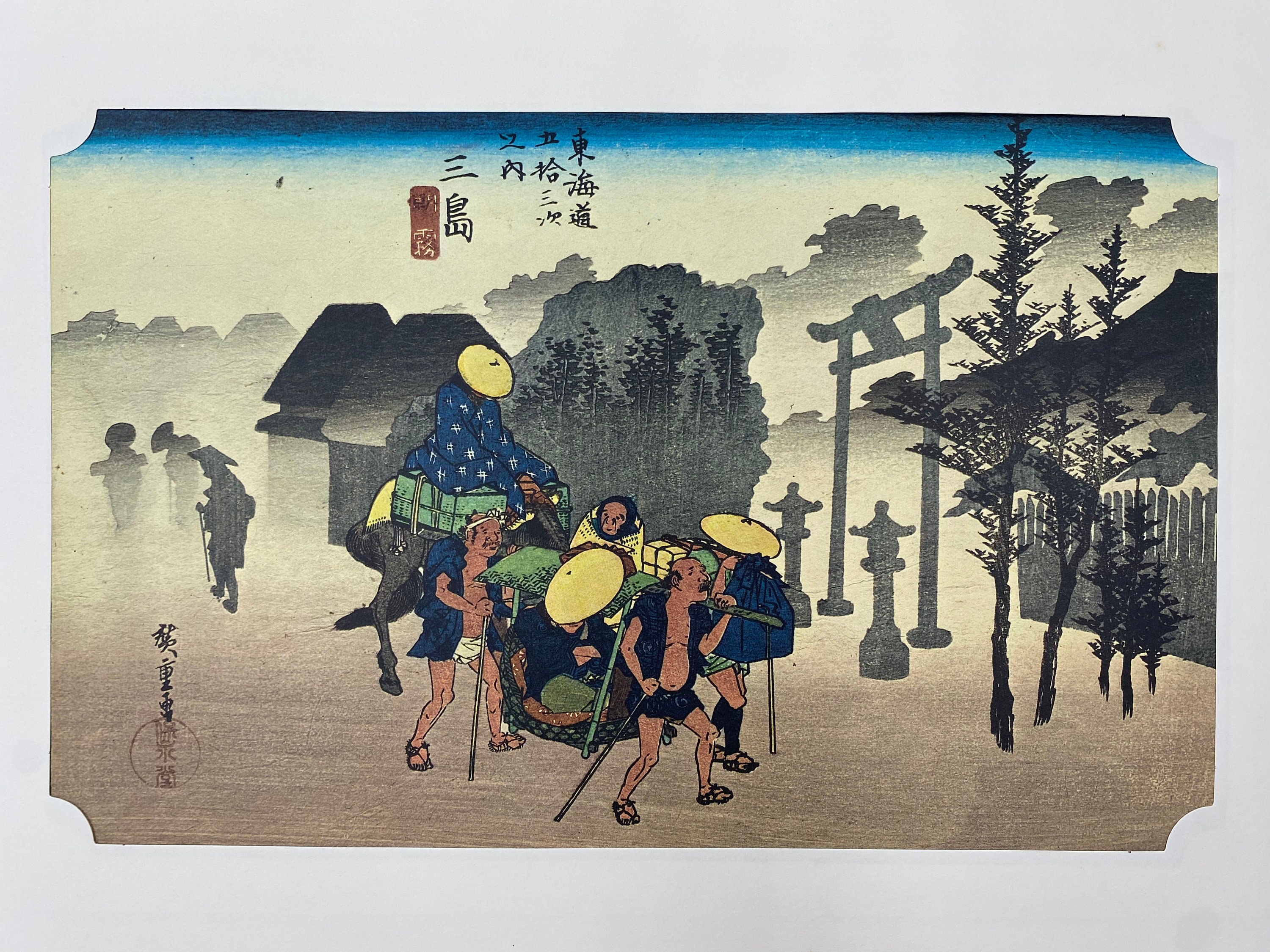

‘Tokaido’ means ‘eastern sea road’, and the line bears that name because it follows – more or less – the route of the centuries-old road that linked the Imperial capital of Kyoto with the Shogunate’s headquarters in Edo (now Tokyo), respectively the seats of ceremonial and administrative power. For hundreds of years, thousands of travellers made the 500-kilometre trip between the two cities (and usually back again), the vast majority of them on foot: horses were rare, the road was unsuitable for wheeled transport, and only the very rich and very important could afford first-class travel in the form of a palanquin – although by all accounts that was hardly less arduous an experience than walking. There’s a palanquin in the print below.

|

| Hiroshige, 53 Stations of the Tokaido: No. 11, Mishima |

The journey would generally take two to three weeks to complete, and travellers of course needed rest and recreation along the way. To cater for this – and in some cases to act as police checkpoints – a series of 53 stations or post towns were set up, offering food, lodgings (carefully graded by status of guest) and shrines and temples to pray for onward protection.

The 53 stations, and the road itself, became entrenched in Japanese popular culture partly thanks to the series of woodcut prints by Utagawa Hiroshige, first published in the 1830s. (There are actually 55 prints in the series, as the terminus of the road at either end – Nihonbashi in Tokyo and Sanjo Ohashi in Kyoto – is not numbered.)

I really can’t remember when or how, but at some point during the 2019 visit, reading about the history of this most famous of Japan’s old roads, I conceived the ludicrous idea of recreating an old-style journey along the Tokaido. After all, millions of people have travelled between Tokyo and Kyoto by train, but how many in the past hundred years have made the journey on foot?

Back in Sydney, research ensued. If many Westerners have walked the Tokaido, few have left much trace. In 2000, an English-born, Japan-based academic called Patrick Carey published a very readable and entertaining account of his journey, illustrated with the Hiroshige prints, which I managed to track down at the Japan Foundation library in Sydney. (Incidentally, a note about the author on the inside fly leaf states that he was born in Woodbridge, Suffolk, a town with which I have a strong association from spending many holidays in the area as a child. That seemed like a good omen.)

A year or two after Carey’s trip, an American, James Baquet, writing as The Temple Guy, blogged about his Tokaido walk, which he undertook as part of a larger series of pilgrimages across Japan and elsewhere. It was from his account that I’ve borrowed the idea of basing myself at a series of hotels for several nights each, using public transport to travel to and from the start or end of each day’s walk.

More recently, but still pre-Covid, Rambling Wild Rosie blogged about her trip, which seems to have been undertaken in the depths of winter and to have involved carrying a full pack from one night’s lodging to the next. She’s clearly tougher than me! For Rosie, long-distance walking seems to be a more-or-less full-time occupation.

Other than an unfinished blog of someone who got halfway (or at least stopped writing about it at that point), I haven’t been able to find any other published accounts of a full Tokaido walk in English.

My friend Kumi sent me a link to a blog in Japanese of a young man who made the journey in 2017, and who delightfully based the trip around the conceit of sampling a different craft beer at each of the 53 stations. I’m keen to see how many of the brews he tried I’m able to find myself. A Google translation of the blog – warts and all – is here.

On the whole, though, I get the impression that Japanese who wish to walk the entire Tokaido tend to do so in stages of a day or two at a time, spreading it out over perhaps several years.

Far more common than either of these approaches (all at once or broken into stages) for visitors and locals alike, though, is to walk just one section: usually the one near Hakone, where modern roads and rail divert from the old route and the Tokaido is said to preserve much of its original character, including avenues of cedar pines and cobble paving. Not coincidentally, it’s also one of the steepest sections of the road.

|

| Cobbled paving on the Tokaido at Hakone. (Creative Commons) |

The reality is that most of the original Tokaido has been buried under modern infrastructure: in places busy highways, in others urban back streets and elsewhere rural roads. This is emphatically not a wilderness hike or even, for most of time, anything resembling an Australian bushwalk.

But that is part of the attraction. I hope to discover the ‘real’ Japan, the mundane suburbs and ordinary towns where most Japanese live, far from the tourist hotspots (although there will be some of that as well), where my meagre smattering of Japanese will be entirely inadequate and where I’ll have to muddle through with sign language and Google Translate.

|

| Part of the old Tokaido route near Nagoya (Google Street View) |

My guides will be the notes I’ve made from Carey’s book and the websites listed above, plus a little volume, entirely in Japanese, that seems to have extensive information about attractions and sites of historical interest along the way, along with maps of each section. Parts of the route are also marked on Google Maps (search for ‘old Tokaido’).

I’ll be taking it much more slowly than those travellers hundreds of years ago. For them, time was of the essence and the destination was the point of the trip. I can afford a much more leisurely pace and want to allow plenty of time for diversions and digressions, for visiting shrines and temples and castles and museums, and for food and drink. There’ll also be the odd rest day thrown in. Although I think most of the terrain will be fairly benign, I am conscious of the fact that I’ll be asking my legs to walk 20+ kilometres for days in a row, which is not something they’re accustomed to. I expect to be making frequent visits to onsens (hot baths) along the way to assist recovery.

I plan to update the blog each day, if nothing else to serve as my own record of the journey. And to help spur me on and to provide some wider purpose to this undertaking, I’m encouraging people to donate to the Indigenous Literacy Foundation, which does great work in providing books in English and in Language to remote First Nations communities and whose mission intersects with that of MultiLit’s Closing the Gap project, in which I’m lucky enough to play a minor role. I’m also hoping to raise awareness of the work done by two organisations involved in ear health, particularly among Aboriginal communities, where the link to literacy difficulties is well known: the Hear our Heart Earbus Project based in Dubbo, NSW, and WA’s Earbus Foundation. Please donate if you can.

It’s now a little under three weeks until I depart for Tokyo. Having thought about, dreamed about and planned this trip for so long, I’m finding it hard to grasp the reality of its imminence. To help remind me of the precarious contingency of all our plans, I’ve come down with a dose of Covid, no worse than a cold, which I hope will have entirely cleared by the time I leave. Far, far better to get it now than in two weeks’ time.

|

| Hiroshige, Fifty-three stations of the Tokaido: No.43, Tokkaichi |

Meanwhile, as Hiroshige so delightfully depicted, I’m sure all sorts of surprises and adventures await...

Gambatte Kudasai! I envy you the opportunity, and please let me know if there's anything I can tell you. I still have some notes, pictures, and pamphlets that never made it into my website.

ReplyDelete